More Wasted Time

by

Michael Amatulli

I had only been back in Toronto a few weeks when I overdosed and came to in the Intensive Care Unit at Keelesdale Hospital. All my money and dope were stolen by the people I was with before I went under, and who’d dumped me from their car just a few blocks from the hospital. I was twenty and wired to heroin and cocaine, and had been for three years, using every day to feed my three-hundred-dollar-a-day habit. To keep from getting dope-sick, I robbed convenience stores and the occasional bank teller. Until a few weeks ago, that is, when I was arrested and convicted on two counts of robbery. My lawyer managed to swing a plea bargain for twenty-two months, and avoided me going into the penitentiary system.

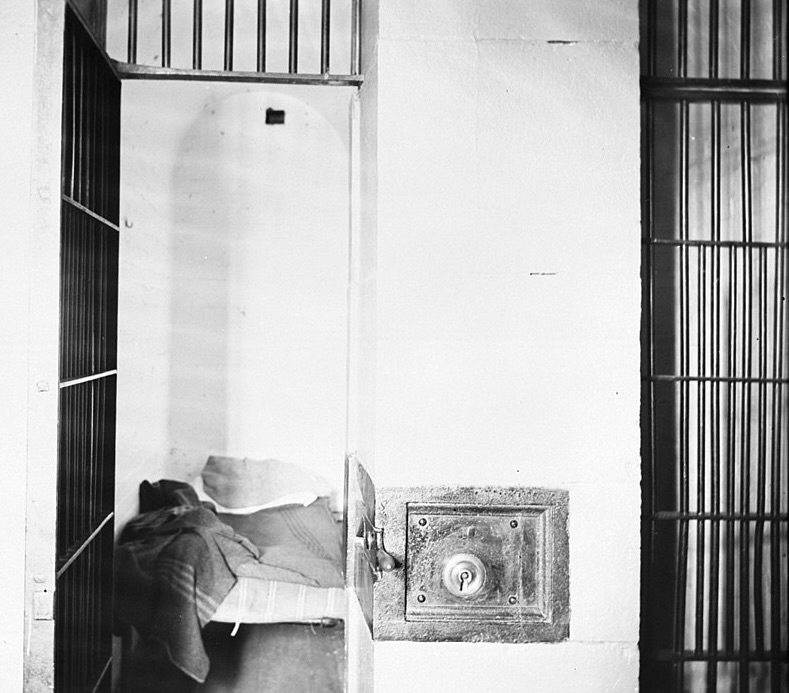

I had previously spent six months in the Don Jail and three in the East Detention for drug possession beefs. This was my first time in a provincial correctional facility, and I did not expect it to be the maximum security Milbrook. I was locked-up every day for twenty-hours, while the remaining four were split between the yard and the range. I was apprehensive about doing time with hardened, violent cons, who were in The Brook because none of the lower security joints would house them – they were considered too high risk. But I quickly adapted, befriending the more notorious offenders from my range, and eventually those from other ranges too, some of whom I knew from the street and others from my time in the Don. It was a matter of reputation to be seen with the higher profile boys, and was the difference between doing easy time, or fighting for every ounce of respect. Whether I won or lost, it hardly mattered; the important thing was not to back down and show fear, which to these guys was an invitation to mess with you.

I spent most of my cell time reading, completing correspondence courses, and writing letters. I hadn’t heard from my younger brother Pino since his first letter, right after he was charged with tossing his ex’s boyfriend over the balcony and nearly killing him. I learned from my mother that Pino was serving time in Guelph and doing well. ‘I can sleep at night knowing you’re both safe,’ she’d written. It’s a hard thing to accept when a mother is more at peace with her children in jail than on the street, though for me the street meant running wild and inching closer to a death by heroin overdose. Or worse, barely surviving the kind of life that made me wish I were dead.

My family resided in Italy, and there wasn’t much our mother could do to help us but worry. The time came, however, when she could no longer stand to be away from us. My father, on the other hand, was against uprooting his family yet again, and would not neglect Angelo and Maria, his two younger children, to help the two older ones, who he believed were old enough to take care of themselves, anyway. Our mother argued that if they did not help Pino and me, we would probably die, an argument our father couldn’t counter, given both of us had already overdosed once – she did not wish to wait around for it to happen again.

Finally convinced, our father sold the shop and apartment. My family arrived in Toronto at the end of July of 1985. It was the first time my father compromised for the benefit of his family, though it wouldn’t be the last.

The days passed quickly in Milbrook, considering I rarely left my cell. It could have been the first day of the month, or the twenty-seventh; it didn’t matter, as each day looked the same, however you turned and shaped it. My cell was ten by ten feet and had a small steel desk and a little window from which at noon exactly, a splash of sun fell on the word ‘fuck’, from fuck the world that some inmate had scatched on it. Instead of meal time, it was fuck time. Of course, a clock wasn’t needed to know what was happening at any given time, in or out of my cell, as after a while, the body became finely tuned and took measurement of the jail, and sensed things, warning when to stay in, or when to come out, and listened to the whispers that passed from cell to cell that told of searches, or when someone was about to get shanked. If you listened closely enough, you could hear the voices moving with the air.

About six months into my sentence I was scheduled to work in the license plate factory. Every day for seven hours I stamped out license plates on an old, industrial press, though I would rather have preferred to stay in my cell to read Dickens, or London, or this guy Bukowski I’d come across in the library, who seemed to have been through the grind himself; or work on the creative writing course I’d recently begun. But a favourable report from the work boss was necessary for the Parole Board to consider an early-release; it showed I could hold down a job and maintain some level of responsibility, which, truth be told, I sorely lacked. I’d never had a job before and my only source of income was crime and street hustle. There was much I needed to learn, if I stood a chance of remaining drug-free, and living past twenty-five, the age many of my friends didn’t reach; guys I’d used and hustled with; went to grade school and played street hockey with; whose mothers still wore black and cried themselves to sleep every night.

I’d managed to stay clean from drugs and alcohol throughout my incarceration, even if heroin and coke could be easily bought with smokes and canteen items. Six months of incarceration had tamed my heroin cravings considerably. I attended the occasional AA meeting also, and went to chapel service every Sunday morning for worship. There was no shame in it, especially not in the Brook, where evil and violence were the dominant themes, and needed to be balanced with Good, or you could lose yourself to the dark side. Besides, where recovery from dope was concerned, a spiritual program was as essential as gravity, the thing that kept me grounded. I felt my energy shifting daily, like the sun, or moon that orients itself around the earth and commands the tides, and so too had God’s light oriented my soul a few degrees to the good; and good begot good. My mind and heart had softened once more, and I prayed and read the bible every day. And good things seemed to happen now, without my asking for it, and I was more grateful for even the little things.

I was called out of work for a visit. It was my first. I was both shocked and relieved to see my parents waiting for me on the other side of the plexiglass partition; shocked that they were there at all, given I believed they were still in Italy; and relieved that my mother was smiling when I entered the nondescript room. My father sat at the stool directly before me, silent in the way only he could be, with a look on his face that suggested he was angry. I was about to say something mundane like, ‘Ciao papa‘,’ when he said,

“Ma, isn’t that George Chuvalo over there?”

I looked over to the stool at the far end of the room and sure enough, there was the three-time Canadian Heavyweight Champ, while on my side of the partition was his son Jesse. The elder Chuvalo was engrossed in some narrative, while the younger listened intently, and then they both laughed, and I wondered how it felt to have that kind of relationship with your father, one where he actually spoke to you, and gave you advice about things, and laughed at your jokes, and said he loved you now and again. I wondered what it was to have a father and a dad.

“E’ Lui, si,” I said, suddenly feeling sadder than when the visit had begun.

George was, of course, hard to miss, being the face of Canadian boxing. His son, on the other hand, had more cause for anonymity. Offenders pestered him about his famous dad, and talked shit behind his back about his family’s struggles with heroin, crap they’d heard in the news, or had contributed themselves through prison yard gossip, passed along like currency from offender to offender. It was difficult enough getting by in this place, without the extra negative attention.

“When did you get here, papa? In Toronto, I mean?”

My father just looked at me without answering. It was his way of controlling us and making you believe you’d done something wrong; of keeping his family on edge and making everything about himself. My father blamed me, you see, for all our family’s struggles, making communication with him almost impossible. And when we did speak, it was strained and forced, awkward even; I had to think hard about the right thing to say. Of course, I understood his animosity toward me; any father would be disappointed whose son had made the kind of poor life choices I had; and besides, what father would be happy with two of his children behind bars. It was much easier to just talk about other people than it was to speak about things that really mattered, the obvious, difficult conversations that might have suggested he was partly to blame for my family’s problems.

“Mamma, why didn’t you mention in your last letter that you were coming here?”

“Vollevamo farti una sorpresa,” my mother said smiling. “A surprise. You look good, Michele. It shows on your face.”

Though she smiled, I saw tears roll from her eyes, eyes that watched me closely, seeking the place where only a mother knows to look, to confirm what I’d claimed in all my letters to her: That I was clean and sober, and had found spirituality once again. It was Faith that gave my mother strength to carry on, and the will to support me and Pino. Knowing I was on a spiritual path validated her efforts. She believed it was her responsibility to teach us about God, protect us from the Devil’s snares, and this from the time Pino and I were alter boys at St. Nick’s; before even, when she tucked us in at night and taught us prayers. I hadn’t yet learned to ride a bike, but I could say the Our Father, Hail Mary, and the entire Rosary, in English and Italian. She was good, my mother was, and knew that in our hearts, so were her sons.

My father continued alternating his attention between me and George Chuvalo, seemingly reassured by the boxer’s presence in the same jail. And not for the man’s social status. It’s true that my father was a proud and private man, and would never tell another person that his boys were criminals and junkies; he was embarassed even to think about it; but here he was now, sitting next to a man, a father, a Champion no less, who’d endured the same emotional blows as him, suffered the same despair and domestic upheaval, and whose son was also a drug addict – my father was reassured by this, and for the moment, didn’t feel quite so alone and helpless.

I instinctively wanted to say how sorry I was for having disrupted their lives again. I’d carried the guilt of my family’s misfortunes since my first fix of heroin at the age of seventeen. Seeing my parents now, I was helpless to deny the depth of my humiliation, and my eyes welled with memories of years wasted on the streets. I understood in that moment the profoundness of their sacrifices; the lengths to which they went in order to keep me from sinking deeper, and deeper still, into my addictions. I wanted desperately to ask their forgiveness; but the words seemed unauthentic in this room, and undeserving. I looked at my parents from behind the glass and saw their innocence, the values they’d attempted to teach me, their goodness. And then I looked to myself and knew that I belonged here, in this shit-hole they called the Brook, a supermax jail likened to Alcatraz. But my parents did not belong, not even as visitors. They were the victims of my recklessness and deserved more than to see their eldest son incarcerated, wearing jailhouse blues and a number on his chest, when their hope for me was to simply be a good man, find a decent job and raise a family, everything I wanted for myself, in fact, but struggled to acquire.

My visit ended and I was escorted to my cell by a Correctional Officer. The mechanical door slammed behind me and I lay on my bunk and picked up John Fante’s Ask The Dust and I read, and read, but the words were merely distant whispers, and melted with thoughts about my life outside these walls, about making my parents proud and getting a job and birthday parties; of hopeful things, the kind of stuff that made one vulnerable in a place like this, where distractions got you killed.

The jail noises intruded into my consciousness, white noise like the mechanical whir of the fan, and the opening and closing of cell doors, and the C.O.’s falling footsteps during count, looking into cells for signs of weapons and narcotics and suicide. The hour I’d spent with my parents earlier in the day was another world entirely, another mental time zone, and was now only a distant memory. I felt myself adjusting to the range activities and sounds, like when I was on the street and got ready to rob a bank, my awareness heightened, vigilant, my conscience turned off. I felt my prison attitude returning to my shoulders and chest, now hardened from months of pushing free weights in the yard; felt it on my skin, like armour, or psychosis. I was two people. I was my mother, with her kindness and generous spirit, her soft innocence and light, and hope for a better future. And I was my father, with his ego and defensiveness, his cold, hard demeanour, and dark half in times of insecurity and threat. I was both victim and assailant.

The 11:00 pm count began. We were locked into our cells until 6:00 pm of tomorrow. I looked out the small window, into the obscure night, and allowed my thoughts to wander into a kind of meditation and I prayed the Rosary and offered up my good intentions. I read some Bukowski and knew that he was writing about himself, as the despair that oozed from his words was my despair when I was homeless, or dope sick, or broke and dope sick. I read a blurb of his that said it was important not to try at things, that you wait and if nothing happens, you wait some more. Yet, all I’d done in my life was wait; for inspiration, love, financial security, vocation, freedom; and nothing came but more wasted time that stretched into days and months and years. I was tired of waiting for things to happen, of people and circumstances to control my life. It was time I took back that control. I picked up my pen and wrote a title for a story I’d begun to write for the Creative Writing course: More Wasted Time, by Michael Amatulli. I finished the story late in the night, and in the silence and stillness of the range, before I went to bed, wrote the final words to close the story:

The End

photo: William James Topley, Carleton County Jail, 1895

public domain, Wikimedia Commons